Issuance of Restriction Order under the Internal Security Act against Singaporean youth and updates on previous ISA orders

28 January 2026

Issuance of Restriction Order under the Internal Security Act against Singaporean youth and updates on previous ISA orders

A 14-year-old Secondary Three student was issued with a Restriction Order (RO)1 under the Internal Security Act (ISA) in November 2025. Investigations found that the youth was self-radicalised online by Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS)’s extremist ideologies, to the extent that he aspired to travel overseas to fight for the group and die as a martyr.

Self-Radicalisation Process

The youth’s radicalisation began in early 2023 (then-aged 12), when he came across an online video of ISIS fighters fighting against American soldiers in Al-Fallujah, Iraq. After watching the video, he started to view ISIS as the defenders of the civilian population against American and Iraqi oppressors. As he searched for more information on ISIS, online algorithms pushed more ISIS-related videos to his social media feed. He also discovered a pro-ISIS website through social media, and spent around nine hours daily consuming the extremist content on this website.

By late 2023/early 2024, the youth had become a staunch supporter of ISIS and its cause to establish a global Islamic caliphate through violence. In June 2024, he took a bai’ah (pledge of allegiance) to ISIS, and thereafter considered himself an ISIS member. To showcase his support for ISIS, the youth started posting pro-ISIS content on his social media accounts. This included pro-ISIS videos that he had created using footage from his online gameplay on Roblox and Gorebox. In these gaming platforms, he had recreated ISIS attacks and executions, and role-played as an ISIS fighter killing ‘disbelievers’ or enemies of ISIS (see Annex A for screenshots of the youth’s Roblox and Gorebox gameplay footage which he used to create pro-ISIS videos).2

Aspirations to Travel Overseas for Armed Violence

The youth felt that he was too young at present to physically take up arms for ISIS. Nevertheless, he aspired to travel in approximately 10 years’ time to Syria, Afghanistan, Africa, Iraq, or Bali in Indonesia, to fight for ISIS and die a martyr on the battlefield. To prepare for this, the youth practised close-quarter battle simulations at home daily for up to two hours with his toy AK-47 rifle, where he would role-play as an ISIS fighter attacking the US Army or the Israel Defense Forces, whom he considered enemies of ISIS.

Garnering Support Online for ISIS

The youth went online to garner support for ISIS’s cause and encourage others to engage in armed violence for ISIS. To this end, he created new social media accounts on various platforms, where he would post at least one publicly accessible pro-ISIS video a day. Some of these videos were created by the youth, using images of ISIS fighters, footages of them in battle, and jihadist nasheeds (songs), which he had found online.

Attack Ideations

The youth’s exposure to ISIS content exacerbated his pre-existing unease with the LGBTQ community. After viewing materials on an ISIS-inspired shooting at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida in June 2016,3 the youth believed that members of the LGBTQ community should be killed. He had thoughts of participating in an attack against the LGBTQ community in Singapore using guns, should one be initiated by others. However, he did not develop his violent ideations further.

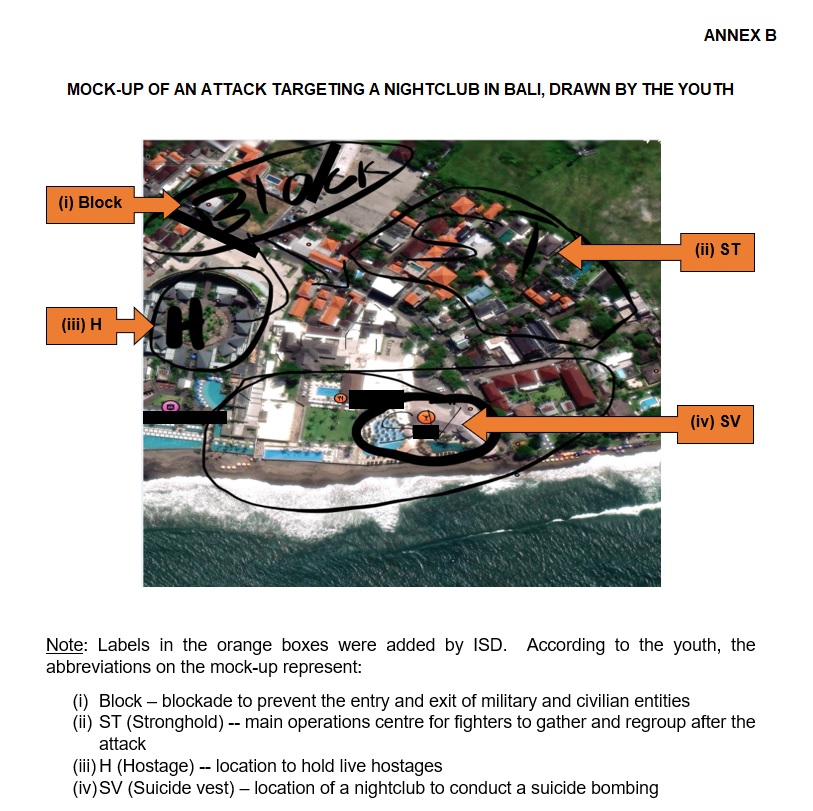

Apart from ISIS, the youth was also supportive of other Islamist terrorist groups such as Al-Qaeda and HAMAS,4 and idolised terrorist personalities such as deceased Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden and ideologue Anwar al-Awlaki, and the perpetrators of the 2002 Bali bombings, in particular Imam Samudra.5 In February 2024, after learning about the Bali bombings from an online documentary, he was inspired by it, and drafted a mock-up of an attack targeting a random nightclub in Bali, using a map which he had downloaded online (see Annex B for an image of the mock-up). He believed that such an attack would further ISIS’s cause to establish a global Islamic caliphate. However, the youth was not found to have developed these ideations further nor made any attack preparations.

Concealing Radical Activities

Aware that his support for ISIS was unlawful, the youth intentionally concealed his online activities to evade detection. Nonetheless, he shared his support for ISIS with his family members and a few of his schoolmates. While several of them attempted to dissuade him, he did not heed their advice. None of them reported him to the authorities.

Continued Concerns with Youth Radicalisation and ISIS Threat

This case highlights why we continue to be concerned with youth radicalisation in Singapore, with a worrying trend of those radicalised getting younger. This youth is the third 14-year-old to be dealt with under the ISA over the past two years for terrorism-related activities.6 They are the youngest individuals to be issued with ISA orders to-date. Youth radicalisation is facilitated by easy access to extremist materials online, and repeated exposure to violence and gore, including on gaming platforms where they can simulate terrorist attacks and role-play as terrorists. This can desensitise the youths to acts of violence, reduce their psychological barriers to harm, and entrench their radical beliefs.7 This case also demonstrates the continued appeal of ISIS’s violent ideologies in Singapore. Since 2020, ISD has dealt with nine self-radicalised Singaporeans under the ISA who were ISIS supporters. Eight of them were youths aged 20 and younger.

Importance of Public Vigilance and Early Reporting

The majority of youths investigated by ISD for radicalisation in recent years had displayed early warning signs to their family and friends, such as expressing support for terrorist groups and the use of violence. In this case, his family members and friends were aware of his extremist views and support for ISIS, but none of them reported him. It was fortunate that ISD detected him before he acted on his violent ideations. However, the authorities may not always be able to detect radicalised individuals before they act. ISD urges the public to seek help from the authorities early if they suspect that somebody close to them might be radicalised. Doing so allows the suspected radicalised individual to get the help they need, and keeps society safe.

The possible signs of radicalisation include, but are not limited to, the following:

a. Displaying signs or symbols of extremist/terrorist groups (e.g., displaying ISIS flag as one’s social media photo);

b. Frequently surfing radical websites;

c. Posting/sharing extremist views on social media platforms, such as expressing support/admiration for terrorists/terrorist groups as well as the use of violence;

d. Sharing extremist views with friends and relatives;

e. Making remarks that promote ill-will or hatred towards people of other races, religions or communities;

f. Expressing intent to participate in acts of violence overseas or in Singapore; and/or

g. Inciting others to participate in acts of violence.

Anyone who knows or suspects that a person has been radicalised, or is involved in terrorism-related activities, should promptly contact ISD at 1800-2626-473 (1800-2626-ISD).

Update on Cases under the Internal Security Act

Release of Self-Radicalised Singaporean Youth from Detention

ISD has released an 18-year-old Singaporean from detention and issued him with a Suspension Direction (SD)8 under the ISA in December 2025, as he had made good progress in his rehabilitation and is assessed to no longer pose a security threat requiring preventive detention. Aged 15 at the time of his detention under the ISA in December 2022, he was an Al-Qaeda and ISIS supporter who was prepared to engage in armed violence and martyrdom operations either in Singapore or abroad, to support the establishment of an Islamic caliphate. The youth had also considered conducting attacks against non-Muslims in Singapore.

During his three years in detention, the youth underwent an intensive rehabilitation programme. He was assigned with two religious counsellors from the Religious Rehabilitation Group (RRG) to address his adherence to Islamist extremist ideologies, and was regularly engaged by ISD psychologists to address the socio-psychological factors that contributed to his radicalisation. These included his permissive attitudes towards violence, and lack of critical thinking skills, which led him to rely on foreign extremist preachers for religious guidance. Two mentors from the RRG guided his personal growth and development, while his family’s weekly visits and words of encouragement motivated him to stay on track with his rehabilitation. The youth has been receptive to these efforts. He no longer holds extremist beliefs nor any animosity towards non-Muslims, and has rejected the use of violence.

As the youth was a Secondary Three student at the time of his detention, ISD made arrangements for him to continue his education, and sit for the GCE ‘N’ (Academic) Level and GCE ‘O’ Level examinations while in detention. In the lead-up to his examinations, he received weekly lessons from tutors, including MOE-trained teachers who are RRG volunteers. He did well for his examinations, performing in the top 20% of his school cohort, and intends to further his studies in an Institute of Higher Learning. ISD will continue to work with his family, school, and other rehabilitation stakeholders to ease his reintegration into society.

Lapse of Restriction Orders

ROs issued against three Singaporeans were allowed to lapse upon their expiry, as they had made good progress in their rehabilitation, and no longer require close supervision under the RO regime:

a. Maksham bin Mohd Shah (aged 44), a self-radicalised individual who had planned to engage in armed violence overseas through joining a foreign radical group. In preparation for this, he underwent physical training in Malaysia, and sourced for weapons and explosives. He was detained in December 2007, and released from detention on a SD in December 2012. He was subsequently issued with a RO in December 2013, which was allowed to lapse in November 2025.

b. A self-radicalised Singaporean, who was detained in January 2020 when he was 17 years old. He was a staunch supporter of ISIS, and was willing to assist ISIS in its terrorist activities, including its online propaganda efforts. He was released from detention on a RO in January 2022, and his RO was allowed to lapse in January 2026.

c. Mohamed Khalim bin Jaffar (aged 63), a former Jemaah Islamiyah member who was detained in January 2002. He was released from detention on a RO in January 2012, and his RO was allowed to lapse in January 2026.

INTERNAL SECURITY DEPARTMENT

28 JANUARY 2026

1 A person issued with a RO must abide by several conditions and restrictions. For example, the individual is not permitted to change his or her residence or employment, or travel out of Singapore, without the approval of the Director ISD. The individual also cannot access the Internet or social media, issue public statements, address public meetings or print, distribute, contribute to any publication, hold office in, or be a member of any organisation, association or group, without the approval of Director ISD.

2 The youth dressed up his in-game character as an ISIS fighter. He would then simulate ISIS attacks against military bases, such as car bombing attacks, sniper attacks, or suicide bombing attacks. He would also simulate ISIS executions by shooting prisoner characters or beheading them using knives.

3 The mass shooting killed 49 and injured 58 others. The perpetrator, Omar Mateen, was an ISIS supporter, and had sworn bai’ah to ISIS during a phone call to the police. He died after being shot by the authorities.

4 The youth became supportive of HAMAS after coming across HAMAS-related material online following the 7 Oct 2023 HAMAS attacks, and saw HAMAS as defenders of Gaza and West Bank. He claimed that his support waned in end-2024 upon learning that HAMAS was purportedly backed by Iran, a Shi’ite Muslim state, as he believed that as a Sunni Muslim, he should not associate with Shi’ite Muslims.

5 Imam Samudra, an Indonesian Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) member, was one of the key perpetrators behind a series of terrorist attacks on 12 Oct 2002 in Bali, Indonesia, which included the bombing of two nightclubs and the US consulate, which killed 202 people and injured 209 others. He was convicted and sentenced to death, and executed with two other perpetrators in 2008. The youth had perceived the attacks as a legitimate response to the consumption of alcohol and the free-mixing of opposite genders in nightclubs, which he saw as affronts to Islam.

6 The other two youths are:

i. A then-14-year-old youth who was a HAMAS supporter and aspired to fight for the prophesised Black Flag Army. He was issued with a RO in June 2024.

ii. A 14-year-old youth who was self-radicalised by a ‘salad bar’ of extremist ideologies; he was a staunch supporter of ISIS, but concurrently subscribed to anti-Semitic beliefs espoused in far-right extremist ideologies, and identified as an incel (involuntary celibate). He was issued with a RO in September 2025.

7 Other than this 14-year-old youth, other self-radicalised Singaporean youths have also simulated terrorist attacks and role-played as terrorists in online gaming platforms. These include:

i. A then-16-year-old ISIS supporter who had joined multiple ISIS-themed Roblox platforms, where game settings replicated physical ISIS conflict zones, such as those in Syria and Marawi in the Philippines. He had used footage from his ISIS gameplay to create ISIS propaganda videos. He was issued with a RO in January 2023.

ii. Then-18-year-old far-right supporter Nick Lee Xing Qiu (Lee) who role-played as far-right terrorist Brenton Tarrant (Tarrant) in an online simulation game, re-enacting the Christchurch mosque shootings and allowing him to simulate his fantasy of killing Muslims. The role-playing also contributed to Lee’s real-life desire to conduct a Tarrant-style attack on Muslims at a mosque in Singapore. He was detained in December 2024.

8 A Suspension Direction (SD) is a Ministerial direction to suspend the operation of an existing Order of Detention. The Minister for Home Affairs may revoke the SD and the individual will be re-detained, if he does not comply with any of the conditions stipulated in the SD. The SD conditions are similar to the RO conditions.

Content Warning: The following contains images that may be distressing to some audiences.